Iron Blue

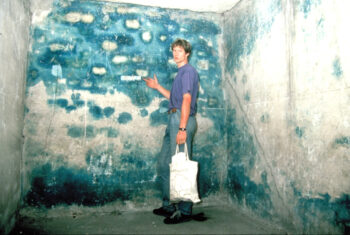

Inside wall of fumigation chamber BW 5a, Birkenau.

Inside wall of fumigation chamber BW 5a, Birkenau. Inside wall of fumigation chamber, disinfestation annex, Majdanek.

Inside wall of fumigation chamber, disinfestation annex, Majdanek. Inside walls of fumigation chamber, Building #41, Majdanek.

Inside walls of fumigation chamber, Building #41, Majdanek. Inside walls of fumigation chamber, Stutthof.

Inside walls of fumigation chamber, Stutthof.Iron Blue is the standard name for a broad variety of pigments formed of iron and cyanide that can exhibit a variety of hues, ranging from dark blue to greenish turquoise. It is formed of a mixture of bi- and trivalent iron cations in the presence of cyanide anions. Other names frequently used are Prussian Blue, Turnbull’s Blue and Berlin Blue. As long as it is not subjected to alkaline, reducing or oxidizing environments that disturb its balance of bi- and trivalent iron, the pigment is very stable and insoluble, and as such non-toxic, despite its high cyanide content.

Iron Blue can form within masonry material if it is exposed to hydrogen cyanide (HCN), such as during fumigations or homicidal gassings using Zyklon B, with its active ingredient of HCN. The formation of this pigment inside masonry when exposed to HCN occurs most readily when the wall – made of plaster, mortar, cement or concrete – is moist and cool, and ideally, not fully set.

Almost all types of cement and sand contain considerable amounts of trivalent iron (as rust). Cyanide itself is a powerful reducing agent in unset (alkaline) mortar and cement, and easily capable of reducing some trivalent iron to bivalent iron, thus allowing the blue pigment to form. The formation of Iron Blue in relatively fresh masonry is well documented. This is true both for former German wartime fumigation chambers, and for accidental damages during the 1970s, in which structures that had been freshly replastered were then fumigated with Zyklon B.

The camps at Auschwitz (Main Camp), Birkenau (two structures), Majdanek (two structures) and Stutthof all contain Iron-Blue-stained walls within fumigation chambers, both on the interior and exterior surfaces, and within the walls themselves. These blue discolorations have survived to the present day (see the many color illustrations in Rudolf 2020). The two civilian structures damaged in the 1970s concern the churches at Untergriesbach and Meeder-Wiesenfeld, both in Bavaria.

Importantly, none of the remaining masonry in rooms alleged to have been homicidal gas chambers at Auschwitz exhibit any discoloration due to Iron Blue. Wall samples analyzed for cyanide residues show no significant traces of cyanide above the detection limit either.

Since the physical conditions of some of these walls (cool, damp basement morgues of Crematoria II and III in Birkenau, made of long-term alkaline cement plaster and mortar) were more conducive to forming the pigment than the walls of the Auschwitz fumigation chambers (warm, dry, above-ground rooms made with only briefly alkaline lime mortar), the lack of any cyanide traces can be explained only by the lack of any significant exposure to HCN fumes. Consequently, such rooms can never have been used for the mass-gassing of people using Zyklon B. (For details, see Rudolf 2020, esp. pp. 27-29, 181-226, 299-361.)

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)