Fumigation Gas Chamber

When the link between infectious diseases, bacteria and bacteria-carrying pests (like insects or rodents) was discovered during the second half of the 19th Century, it quickly became apparent that this was a pivotal event in the history of human healthcare. Some of these pests were the vectors of major epidemic diseases, such as the body louse for typhus bacteria, and fleas for the plague.

While the plague was very much under control in the 20th Century, typhus was not. This often-lethal disease was still widespread (endemic) in Eastern Europe, where sanitary equipment was often very primitive, if it existed at all, and thus hygienic conditions were poor, treated water was unknown, sewage systems did not exist, and primitive outhouses were the standard everywhere. Lice and flea infestation was therefore quite common for all populations that could not (or would not) bathe, did not wash their clothes and bed linens regularly, and where there were no means of exterminating pests.

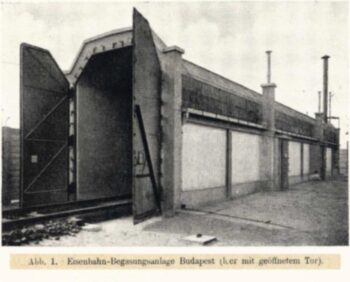

By the time of World War One, Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s Eastern borders were also the borders that separated hygienically advanced Central and Western Europe from areas where primitive hygienic conditions allowed diseases such as typhus to persist. It was in the first decades of the 20th Century that Germany started equipping its eastern border railway stations with large rail-car fumigation chambers, allowing the disinfestation of rail-cars coming in from Eastern Europe.

The increased and often uncontrolled traffic of soldiers, civilians and merchandise between Central and Eastern Europe during both world wars led to hygienic crises in Germany, as lice infested with typhus bacteria were reintroduce in masses in Germany. Hot spots of those infestations were the various camps (refugee, labor, PoW, concentration, transit camps etc.) where people were housed in close quarters under poor hygienic conditions.

After World War One, a newly established German company, DEGESCH, became a leader in developing disinfestation gases and fumigation chambers, and issued licenses for their production and distribution. Among the various methods used were hot steam, hot air, T-Gas, Areginal, Tritox, carbon monoxide produced by producer-gas generators, and Zyklon B. In German camps of the Second World War, hot steam and hot dry air, as well as Zyklon B, were commonly used for disinfestation purposes in a desperate attempt to control typhus epidemics. While hot steam and hot air also act as a disinfectant, meaning they also kill bacteria, Zyklon B does not; it merely kills the pests, such as lice or mice, that carry the bacteria. However, hot air and steam can damage fumigated objects, hence they are not suitable for all applications. In many cases, Zyklon B was the preferred method. Toward the end of the war, new techniques like DDT powder and microwave delousing facilities were introduced for pest-control at the Auschwitz Camp.

In principle, any enclosed or closable space can serve as a fumigation chamber, if the acting gas can be released in it in sufficient quantities during the gassing procedure. If the acting gas is poisonous to humans, and if the fumigated space is not air- or gas-tight, safety precautions must be taken to keep unprotected people away from the space by warning signs, physically isolating the gassing facility (fences, walls, etc), and possibly by guards.

Carbon-Monoxide Fumigation

Already before World War One, the German medical professors Bernhard Nocht and Gustav Giemsa developed a fumigation method using carbon monoxide produced by a producer-gas generator. This device burned wood, coal or coke with limited amounts of oxygen, thus producing a gas that contained high amounts of carbon monoxide (CO). Since insects are not sensitive to carbon monoxide, this method is only suitable to kill warm-blooded pests, such as mice and rats. Before, during and after World War One, it was a very common method to combat mice and rats in freight ships.

Due to extreme shortage of any petroleum-based fuel in Germany during World War Two, the entire German road-transportation industry, incentivized by government decrees and subsidies, increasingly switched from liquid fuel to gas by installing mass-produced versions of producer-gas generators similar to those used for the Nocht-Giemsa fumigation method. In fact, these industrial models produced a gas that contained even more CO than the models used for fumigation, hence they were even more lethal. These devices were installed on trucks, buses, vans and even tanks. Their CO-rich gas was fed into the engine as fuel. Every German vehicle engineer knew about them during the war. They were easy to procure, cheap to operate, had endless fuel, and their gas would have been instantly lethal. In fact, specialists for fumigation and disinfestation, among them those who developed, produced, sold and applied Zyklon B, most likely knew these devices from the Nocht-Giemsa method. But there are no reports of any such device ever having been misused for murder, although they would have been the logical choice. (For details, see Rudolf 2024a, pp. 453-455.)

Zyklon-B Fumigations

Fumigations using the pesticide Zyklon B (hydrogen cyanide) became one of the most-commonly used methods of pest control between the two world wars. Initially, fumigation chambers were nothing more than ordinary rooms with sealed doors and (perhaps) windows, a heat source for the room, and equipment for some means of ventilation. The Zyklon B carrier material – a chalk-like gypsum in the form of small pellets – soaked with liquid hydrogen cyanide, was simply spread out on the floor by a fumigation expert wearing a gas mask, who then retreated and locked the door. The gassing process could take many hours, even up to a day or two, depending on the size of the room, the type and density of materials placed in it, the room temperature, and the gas concentration reached with the applied quantity.

If there were any leaks in the chamber, or the heating system extracted any air (and thus also gas) from the chamber, concentrations could sink over time and reduce the efficacy of this method. Also, since the gas had to diffuse into the target objects, thick or dense objects might never become fully saturated, and thus complete success was never guaranteed.

Due to the many safety risks, German wartime regulations prescribed certain safety measures for these types of fumigation chambers:

- Whenever a person wearing a gas mask entered a fumigation chamber containing, or about to contain, poison gas, a second person had to remain outside behind the closed door, also wearing a gas mask, so that he could rush to help in case of an emergency.

- That second person had to observe the other entering the chamber through a window or (better) a peephole in the door.

Furthermore, since clothes to be fumigated were typically brought into these chambers hanging on metal racks on wheels, which might bang against the door, the peepholes were to have a metal protection grille on the inside to protect the glass pane from getting cracked by the metal racks. Multiple doors found in Auschwitz used to enclose fumigation chambers had such grille-protected peepholes. (See the entry in gastight doors.)

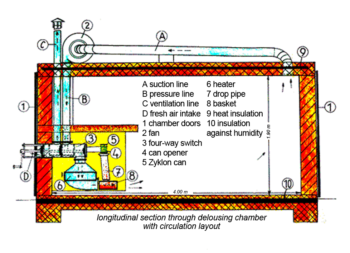

This haphazard and dangerous nature of Zyklon-B gassings was overcome only when DEGESCH introduced their so-called Normal Gas Chamber. In such a chamber, the room was sealed hermetically, heated electrically, and allowed remote opening of a Zyklon-B can and the dispersal of its pellets. Additionally, a heating device blew warm air over the pellets to evaporate and dissipate the gas quickly, and circulated the air in the chamber constantly to accelerate the procedure. Finally, there were ventilation mechanisms for quickly and safely evacuating the poison gas; see the construction drawing of a Normal Gas Chamber in the illustration.

The fumigation chambers at Dachau included similar systems, which still exist to this day. Nineteen such chambers were planned for the Auschwitz reception building, but they were never installed because the building construction proceeded quite slowly, and because an even newer and more-advanced system, based on microwaves, soon emerged, causing the camp administration to delay installation of any new Zyklon chambers.

(For further information, see the entry on microwave delousing, as well as Berg 1986, 1988; Rudolf 2020, pp. 68-90; 2019a, pp. 18-26.)

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)