Ventilation

Principles

By “ventilating” an enclosed space, we refer here to replacing old, stale or contaminated air with fresh, uncontaminated air. In an ideal scenario of a cuboid space (room), fresh air would be pushed in along the entire surface area of one end of the room, and stale air would be taken out along the entire surface area at the opposite end. With a laminar air flow, hence without any turbulence, a complete replacement of the entire air would happen after a fresh air volume equivalent of the room’s volume has been pushed in. However, such an ideal setup does not exist in reality. Air inlets and outlets never cover the entire surface area of a wall, inlets and outlets are not always located at opposite ends of a room, and turbulences always happen. In fact, since the quantities and locations of inlets and outlets are never ideal, air turbulences are even necessary, so that air in areas that are not located along straight lines from inlets to outlets, is replaced as well.

A turbulent exchange of stale air with fresh air requires much more time to achieve a complete replacement of all air, since some of the fresh air inevitably gets expelled together with stale air. In cases of perfect mixing of fresh air with stale air, pushing in one complete room volume of fresh air leads to only some 2/3 of the stale air getting expelled, together with some 1/3 of fresh air. This partial reduction of remaining stale air continues with every new air exchange, so the fraction of stale air still in the room decreases exponentially with time. Of course, perfect mixing does not always happen either, so there will be areas in the room where the scenario is closer to a laminar air flow – along straight lines between inlet and outlet – and areas where mixing is occurring only slowly – in pockets distant from any air inlet and outlet. In the latter regions, the reduction of stale air is even slower.

In this context, it matters little whether “stale air” means merely a reduced amount of oxygen, or the presence of unpleasant smells, high humidity, aerosols or some toxic component.

Fumigations/Disinfestations

Any enclosed space can be disinfested with a gaseous chemical that is toxic to the targeted infesting organism. Wartime instructions issued by DEGESCH, the company that held the patent for Zyklon B, indicate that buildings disinfested with Zyklon B can be aired out with natural draft (without giving a time), once all windows and doors are opened, and provided that the premise is not tightly filled with objects (see Leuchter et al. 2017, p. 84). Wartime instructions issued by German authorities during the war stipulated that buildings disinfested with Zyklon B which do not have a forced (mechanical) ventilation ought to be air out for at least 20 hours (Nuremberg Document NI-9912, see Rudolf 2016, pp. 122f.).

A dedicated fumigation gas chamber usually has some ventilation system accelerating the airing-out process, either by sucking out the room’s air with a fan, replacing it with air coming through a door, for example (which, when using a disinfestant toxic to humans, can be dangerous in the case of fan failure or opposing wind conditions), or by installing two fans, one of which extracts air, while the other feeds in fresh air. Under optimal conditions, these fans are located at opposite ends of the room.

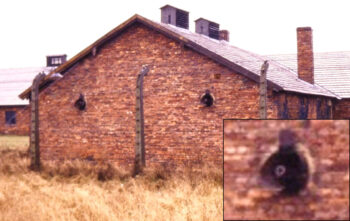

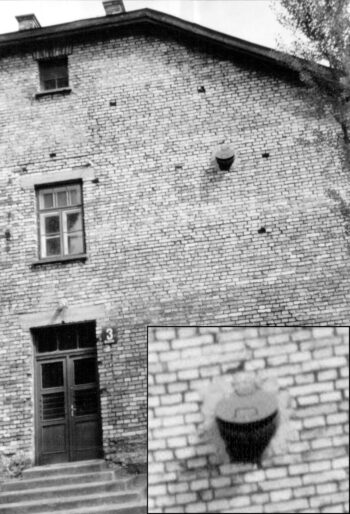

In German wartime camps, we find examples of dedicated Zyklon-B-fumigation gas chambers of a more rudimentary nature without mechanical ventilation (for instance at the Stutthof Camp, see Graf/Mattogno 2016, pp. 117-124), or with just one or two air-extraction fans set in one wall (at the Auschwitz Main Camp and at Birkenau, respectively, see Mattogno 2016f, pp. 240f.). Ventilating these facilities would have taken many hours before they could be entered without protective gear.

Furthermore, professionally designed Zyklon-B fumigation gas chambers existed, such as the DEGESCH circulation chambers. These devices had powerful blowers that sucked in and extracted a volume of fresh air equal to the chamber’s volume within less than a minute, hence going through more than 60 complete air exchanges per hour, allowing for a swift ventilation in much less than an hour, even if the chamber was stuffed with fumigated objects (see Rudolf 2023, pp. 127f.). Four such systems were installed at the Dachau Camp, where they are exhibited to this day.

Morgues

Every morgue, no matter the place and time of its existence, needs an efficient ventilation system to prevent the smell of rotting corpses from filling the place. A classic standard work on German architectural norms stipulates that a morgue requires a minimum of five air exchanges per hour and 10 during intensive use, such as in cases of war, natural disasters or epidemics.

Epidemics caused by the effects of war were exactly what Germany’s wartime camps were facing. Hence, the ventilation systems planned and installed inside the morgues of the Birkenau Crematoria II and III had a capacity at the upper end of this range (see Rudolf 2016, pp. 173-176):

- Morgue #1 (the alleged homicidal gas chamber) had a capacity of 9.5 air exchanges per hour.

- Morgue #2 (the alleged undressing rooms) had 11 air exchanges per hour.

There were other systems in those buildings with higher capacities:

- The system serving the ground-level work area of the physician (dissecting room, laying-out room, washroom) had a capacity of some 10 air exchanges per hour.

- The furnace room’s ventilation system had a capacity of 9.7 air exchanges per hour.

We see that all systems were designed to have roughly 10 air exchanges per hour, hence at the upper end of architectural recommendations, as is to be expected.

Note that the room presumably misused as a homicidal gas chambe had a system that was not significantly different from all the other rooms, indicating that it was not planned to serve a sinister purpose. This design had been planned since the inception of that building in late 1941, hence at a time when even the orthodoxy agrees that no plans existed to misuse the facilities for mass homicide. This change in the room’s purpose supposedly occurred sometime late 1942, but it did not result in an increase in the ventilation capacity of Morgue #1. This means that, from a technical point of view, its planned function did not change. (See Rudolf 2023, pp. 127f.; Mattogno/Poggi.)

Little documents have survived indicating what ventilation systems, if any, were installed in Crematoria IV and V in Birkenau. Evidently no such system was ever ordered or installed for Crematorium IV. A system ordered for Crematorium V seems to have been either never installed or only toward the summer of 1944. The drawing showing its design has been lost, so it is not clear which rooms were to be serviced with this system, which makes calculating a capacity speculative (See Mattogno 2019, pp. 156-158).

The morgue of the old crematorium at the Auschwitz Main Camp, which supposedly served as a homicidal gas chamber on an unknown number of occasions between late 1941 and early 1942, was never equipped with a professionally designed ventilation system. In late 1940, the Topf Company had offered a system for the morgue providing for 20 air exchanges per hour. The camp authorities ordered a re-designed system in mid-March 1941, but since the delivery time was long, a makeshift solution was implemented connecting the morgue to the smoke duct of one of the two cremation furnaces next door, thus using the chimney’s draft to suck out air from the morgue. This system worked so badly that it was decided in June 1941 to add fans in the building’s roof, which were installed in early fall of 1941. The exact design is unknown, as no description or drawing has been preserved, but it has nothing to do with homicide, as the planning period (early June 1941) is well before any decision was allegedly made to commit mass murder at Auschwitz, let alone to convert this morgue for that purpose.

The professional ventilation system by the Topf Company was delivered in late 1941, but by late 1942, at a time when the homicidal gassings claimed by the orthodoxy for this facility had allegedly ceased, it had still not been installed. Hence, that morgue never had a professionally designed ventilation system during the time span when it was supposedly misused for homicidal gassings. Furthermore, the camp authorities evidently saw no reason to install the delivered system at a time when they were allegedly misusing this room for mass homicide with toxic gases. This indicates that no homicidal gassing ever occurred in that room. (See Mattogno 2016f, pp. 17-23.)

Homicidal Gassings

Real-world data about the ventilation of homicidal gas chambers can be gleaned from the hydrogen-cyanide gas chamber systems once used in some U.S. states for capital punishment. After an execution, the chamber’s powerful ventilation system carried out numerous air exchanges within fifteen minutes, after which the chamber was entered with protective gear to remove the victim. The fan was left running until the next day to ensure that any residues of the toxic gas were removed. (See Leuchter et al. 2017, p. 205.)

The necessity and technology of ventilating any claimed German wartime mass-execution chambers would have depended on the toxic gas claimed to have been used.

In the case of engine-exhaust gasses, as claimed for the gas vans as well as for stationary chambers at the camps at Belzec, Sobibór and Treblinka, mechanical ventilation systems would not have been required, because the exhaust gases allegedly used were not highly toxic: diesel-engine exhaust gases were not lethal in the short run at all, and gasoline-engine exhaust gases would have required extended exposures to full concentrations to have an effect. Therefore, natural ventilation by simply opening doors at both ends of a room filled with such gases would have swiftly rendered the air in such rooms non-lethal under any circumstances. Since the lethal component of exhaust gases – carbon monoxide – is not water soluble and thus does not accumulate on wet bodies, a large pile of entangled bodies, though slowing air movement down, would not have caused a major challenge, as the amount of exhaust fumes lingering between corpses would not have been enough to kill anyone when moving a body.

The situation is drastically different when using Zyklon B, meaning hydrogen cyanide, however, as is claimed for the camps at Auschwitz Main Camp, Birkenau, Stutthof, and also Majdanek (at least claimed in the past), as well as a string of minor events claimed in western camps (see the entry on homicidal gas chambers). Hydrogen cyanide is much more toxic than carbon monoxide, and it is also highly water soluble, making it accumulate on moist surfaces. This results in much longer ventilation times, and thus the need for powerful mechanical ventilation systems.

The scenario of hundreds or thousands of humans tightly packed into an execution chamber leads to complications comparable to fumigations of moist laundry and clothes that greatly exacerbate the already difficult ventilation challenge:

- During fumigations, clothes and linens are put on hangers on fumigation racks, hence they hang loosely. Consequently, fresh air can freely flow around and through them, facilitating the venting process. However, air cannot move freely around and through a large pile of collapsed humans lying on top of each other. In fact, ventilating the air around and underneath those victims becomes almost impossible.

- During fumigations, air temperatures were kept warm, in part to make sure that the clothes and linens are dry, so that no gas gets absorbed in any humidity. However, human skin is by definition moist, and even more so when under stress in a struggle for life and death, not to mention any bodily fluids released in the ensuing panic. Therefore, a large pile of dead humans, moist for numerous reasons, would have absorbed considerable quantities of hydrogen cyanide, further prolonging any ventilation process.

For these reasons, the minimum duration for a successful ventilation of a fumigated premise mentioned in German wartime instructions – 20 hours if not more – would have applied most certainly to any mass gassing in large rooms that did not have any mechanical ventilation equipment. In fact, considering the knowledge and skills of German experts on fumigations with Zyklon B as demonstrated by the forced-ventilated fumigation chambers built in many wartime camps, it is inconceivable that any mass-execution chamber applying Zyklon B ever would have been built without a powerful mechanical ventilation system. Any claims to the contrary can be safely dismissed as wartime propaganda.

Furthermore, any claim that such mass-execution rooms not equipped with mechanical ventilation systems were entered instantly or within 10, 20 or 30 minutes of opening the room’s doors and/or windows merely serves to highlight the physically impossible propaganda nature of these claims.

In the case of Auschwitz, this applies to homicidal gassing claims in the so-called bunkers of Birkenau, in Crematorium IV, and any such gassings in Crematorium V before the summer of 1944, none of which are said to have had any ventilation systems. To make matters worse, Zyklon B is said to have been poured amongst the inmates in these facilities, releasing its poison slowly for at least an hour, and perhaps up to two hours, depending on ambient conditions. Hence, no ventilation success could have been achieved at all before all hydrogen cyanide had evaporated.

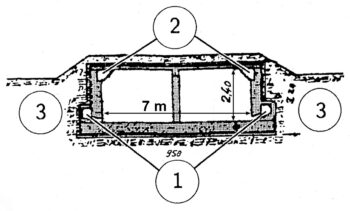

Although Morgue #1 of Crematoria II and III in Birkenau, the alleged homicidal gas chamber, had a ventilation system, it was clearly planned and designed for a morgue, not for homicidal gassings. It was moreover badly designed, as air intake and outlet were located on the same wall, only some 2 m apart, so that fresh air blown in through the inlets near the ceiling was to a large degree sucked out again through the outlets near the floor rather than flowing across the 7-meter-wide room to the outlets on the other side. Hence, air in the center of that room was poorly ventilated.

Using an unheated basement room with inevitably cool and moist walls for gassings with Zyklon B is a very bad idea, since cool and moist walls absorb large quantities of the poison. When aired out, the walls then slowly release the absorbed poison, slowing the ventilation process. Moreover, the air-extraction openings in these rooms were located at floor level, where dead bodies would have obstructed them at least partly, further slowing the ventilation process. (See Mattogno/Poggi.)

A successful ventilation in these rooms would have depended on whether the applied Zyklon B could be removed after the gassing, which depends on the nature of the Zyklon-B introduction device claimed for this room (see this entry). Without the ability to remove the poison, successful ventilation would have lasted several hours. In case Zyklon B could be removed, the duration could be reduced to maybe an hour, although pockets of gas would have persisted among the piles of bodies. Claims that the doors were opened only minutes after the execution and that the bodies were removed right away are simply false.

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)