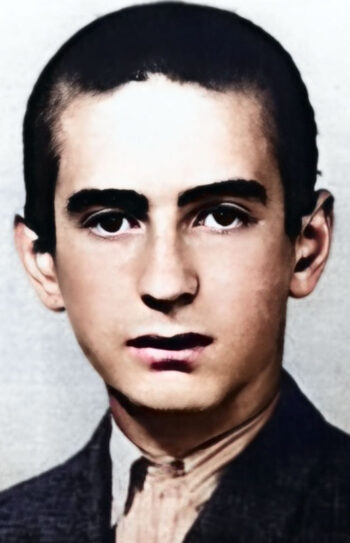

Wiesel, Elie

Elie (Eliezer) Wiesel (30 Sept. 1928 – 2 July 2016) was a Romanian-born Jew who claimed to have been deported in May 1944 to Auschwitz at age 15 with his entire family, including his 50-year-old father, from what was then Hungary. When the Auschwitz Camp was evacuated, Wiesel claimed that he and his father Shlomo Wiesel decided to join the Germans retreating west. The Wiesels eventually ended up at the Buchenwald Camp, where Elie’s father died shortly before the camp was liberated by U.S. troops on 11 April 1945.

The problem with this story is that admission records of both the Auschwitz and the Buchenwald Camps show only the admission of an Abraham Wiesel, born in 1900, hence 44 years old in 1944, and a Lazar Wiesel, born 4 Sept. 1913, hence 31 years old in 1944, too old to be Elie or to be accidentally confused with him. Abraham Wiesel was six years younger than Shlomo Wiesel’s claimed age, and the first names don’t match. There is no trace in any German camp record of any man with the last name Wiesel or similar who was born in or around 1928. Therefore, Elie Wiesel was probably neither ever in Auschwitz nor in Buchenwald, and Abraham Wiesel may also not have been Elie’s father.

After the war, Wiesel first lived as an orphan in France, and later immigrated to the United State. Not too long after the war, Wiesel wrote an allegedly autobiographical text in Yiddish about his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, titled Un di velt hot geshvign (And the World Remained Silent), which was published in Argentina in 1956. An adapted French translation of it was eventually radically rewritten by French author François Mauriac, to live up to his literary expectations, and published in 1958 with the title La Nuit (Night). Translations in all major and many minor languages followed in subsequent decades. The book has become required reading for students at many high schools, colleges and universities around the globe, and is probably one of the most influential Holocaust texts.

The text has numerous false claims that radically undermine the credibility of its author, among them for example (based on the original French edition; other translations have been cleansed of some of this nonsense):

-

- Wiesel claimed that they were deported in early June 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz in April 1944 – yes, he traveled backward in time! The admission records for Abraham and Lazar Wiesel in Auschwitz show 24 May 1944.

- Wiesel claimed that, in the cattle car crammed full of frightened and suffering Jews on their way to Auschwitz, the young orthodox Jews in the car had a sex orgy. That passage, based on a young man’s perverted sexual fantasy but certainly not on reality, was censored out in all foreign and also all later French translations.

- Wiesel wrote how the inmates locked up in the railway cattle car could see flames spewing out of large chimneys into the black of the night, as the train was approaching the Birkenau Camp. However, no flames can come out of crematorium chimneys whose furnaces are fired with coke.

- Wiesel followed the cliché that every Auschwitz inmate, he and his father included, was selected by Dr. Josef Mengele, whom he described as a “typical SS officer, cruel face, […] and a monocle,” which is the opposite of Mengele’s complexion, who wore no glasses and looked rather friendly.

- After passing the initial Mengele selection on the railway ramp, Wiesel and his father kept on walking, when they saw nearby two large fire pits. Into one of them, a truck dumped living babies, and the other, larger one was meant for adults. However, air photos of exactly that time show no such burning pits anywhere in the area, and even the orthodoxy agrees that no burning pit was located anywhere near the railway platform, so Wiesel described something that everyone agrees didn’t exist.

- During his entire text, Wiesel never used the term “gas chamber,” but only the word “crematorium.” This annoyed the translator of the German edition so much that he replaced all instances of “crematorium” with “gas chamber,” including two cases in the section about the Buchenwald Camp, where everyone agrees no homicidal gas chamber existed.

- Wiesel described the hanging of a child, suffering because its low weight didn’t break its neck when the stool was pulled. Scholars agree that children were not sentenced to death and killed like that at Auschwitz. It is an allegorical scene.

- On 18 January 1945, when the Auschwitz Camp was evacuated, sick or injured inmates who had difficulties walking were given the choice to either stay and wait for the Soviets, or leave with the retreating Germans. Elie wrote that, after some contemplation with his father, and in spite of rumors that those left behind might get executed – a risk that was even higher when they left with the Germans – they decided anyway to leave with the Germans rather than wait for the Soviet liberators. Here is how U.S. engineer Fritz Berg described this pivotal decision:

“The choices that were made here in January 1945 are enormously important. In the entire history of Jewish suffering at the hands of gentiles, what moment in time could possibly be more dramatic than this precious moment when Jews could choose between, on the one hand, liberation by the Soviets with the chances to tell the whole world about the evil ‘Nazis’ and to help bring about their defeat – and the other choice of going with the ‘Nazi’ mass murderers and to continue working for them and to help preserve their evil regime. […]

The momentous choice brings Shakespeare’s Hamlet to mind:

‘To remain, or not to remain; that is the question:’ to remain and be liberated by Soviet troops and risk their slings and rifles in order to tell the whole world about the outrageous ‘Nazis’ – or, take arms and feet against a sea of cold and darkness in order to collaborate with the very same outrageous ‘Nazis.’ Oh what heartache – ay, there’s the rub! Thus conscience does make cowards of us all.”

- Of the 100 inmates traveling on a train to Buchenwald, Wiesel claimed that only 12 survived (88% death rate), although the original records show that the death rate was only about 2%.

Elie Wiesel left Auschwitz with his German captors, because he knew that the truth about Auschwitz was nowhere near what he later wrote in Night, this novel disguised as an autobiography written by a disturbed mind filled with hate and a lust for revenge. This novel may have been his first act of systematic lying, but it wasn’t his last, as Warren Routledge has thoroughly documented in his critical biography of Elie Wiesel. (For more details, see Desjardins 2012; Routledge 2020; Rudolf 2023, pp. 477-480.)

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)