Frank, Anne

Despite her status as perhaps the most famous Holocaust victim, the story of Anne Frank has little direct bearing on the larger Holocaust narrative. In one sense, she was just one more Jewish victim of the evil Nazis. And yet, there is so much controversy around her famous diary that it threatens to expose deeper and more troubling aspects of what might be termed “Holocaust propaganda.” These troubling aspects suggest much about how the conventional Holocaust story is marketed and promoted. Indirectly, then, Anne’s story has value for understanding the present-day phenomenon of the Holocaust.

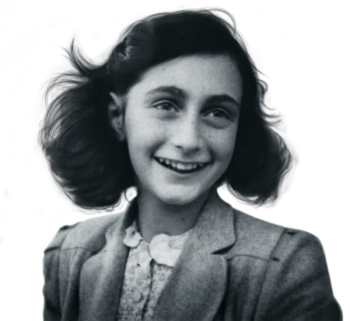

The basics of Anne’s life story are relatively clear. She was born Annelies Marie Frank, in Frankfurt, Germany, on 12 June 1929. She was the youngest of the two Frank girls, her older sister Margot having been born in 1926. Anne’s parents, Otto and Edith, lived a fairly conventional middle-class life in Frankfurt – Otto was a small businessman – until the rise of Adolf Hitler’s National-Socialist party in 1933, at which time they decided to flee to the Netherlands. Anne and her family moved to Amsterdam in February 1934 when she was four years old. There she attended school, becoming quite fluent in Dutch, which became the primary language of the Frank family. Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, putting new pressure on Dutch Jews, all of whom now had to adopt a low-profile existence. Eventually, the Frank family, along with another Jewish family of three and a dentist, went into hiding in an “annex” of her father’s office building in central Amsterdam. They lived in hiding, more or less continuously, for around two years.

Sometime in mid-1944, perhaps early August, the Frank family was exposed, apprehended, and deported to the Westerbork transit camp, and soon thereafter on to Auschwitz in the south of present-day Poland. At Auschwitz, Otto was separated from the three female members of his family. He stayed in the camp until its liberation in January 1945, but the two Frank girls were shipped on to Bergen-Belsen Camp in October 1944. (Edith died in Auschwitz.) Like many camps late in the war, Bergen-Belsen had a large outbreak of typhus. Apparently, both girls contracted the disease and died in February or March 1945. Anne’s body was never found. She was 15 years old.

Unfortunately, these few sketchy details are about all that we can say with certainty about Anne/Annelies Frank. Everything else that we think we know about her is in doubt: what she wrote, how much she wrote, what she did during her 10 years in Amsterdam, what life was like during her two-year “hideout” in the annex of her father’s office building, and so on. Most importantly, we literally do not know how much, if any, of the famous diary was written by her. And if Annelies was not the author of the diary – then who was? When did they write it? And why?

For many years, the most prominent critic of the Anne Frank diary was a French professor of text and testimonial critique, Dr. Robert Faurisson – see in particular his 1982/1985 essay “Is the diary of Anne Frank genuine?” With his passing in 2018, new scholars have taken up the challenge. Among the most important of recent studies is Unmasking Anne Frank (2022) by Japanese scholar Ikuo Suzuki. He cites the following problems and anomalies:

- The rewritten (“B”) version contains numerous trivial and arbitrary changes from the “original” A-version. There is no obvious explanation for this.

- The version made public is a highly edited version of the “B” draft, now called the “C”-version.

- Another Jewish writer, Meyer Levin, got involved with Anne’s father Otto very early on; there is good reason to suspect that he in fact was the author.

- Translations into other languages make arbitrary and factually incorrect translations of many words and phrases.

- There are many irreconcilable problems with eight people living in an attic for two years: food, bathing, trash disposal, toilets, etc.

- Anne includes many highly-mature passages about human sexuality, her own sexual organs, and so on – very unlikely for a 13- or 14-year-old girl.

- Despite being a virtual “genius writer,” Anne wrote nothing more between her deportation in mid-1944 and her death in March 1945, despite many clear opportunities to do so.

- The Germans transferred Anne away from Auschwitz, presumably a “gas-chamber” camp, to Bergen-Belsen, which had no gas chambers.

For Suzuki, all this is evidence that (a) the diary cannot possibly be the actual transcriptions of a teenage girl in wartime Amsterdam, (b) someone – likely Anne’s father Otto and Meyer Levin – conspired to foist upon the world a bogus story of an innocent young girl and her death, and (c) large portions of the Holocaust story itself were likely also edited, embellished, altered and rewritten, as the need arose.

Holocaust critics sometimes like to refer to the “ballpoint pen” issue: “significant” portions of the diary were allegedly written in such a pen, even though it did not exist until after the war. They use this claim as evidence of fraud. In reality, there are only two attached notes written in ballpoint, and clearly distinct from the diary itself. Hence, no serious scholar today cites the ballpoint-pen claim. But orthodox scholars will still bring it up, only to shoot it down, in strawman-like fashion, as a way of distracting from the many other, very serious issues with the diary.

You need to be a registered user, logged into your account, and your comment must comply with our Acceptable Use Policy, for your comment to get published. (Click here to log in or register.)